AI & Digital Health Innovation

Advancing AI research to revolutionize the future of digital healthcare.

We believe that a Team Science approach leads to the best research development. Our researchers span 75 departments across 17 schools and colleges. We support two active communities that provide collaborative interaction for digital health researchers interested in genetics and AI/Machine Learning. Whatever area of interest you have, we can help you find a collaboration partner to advance your research.

Team Science Support

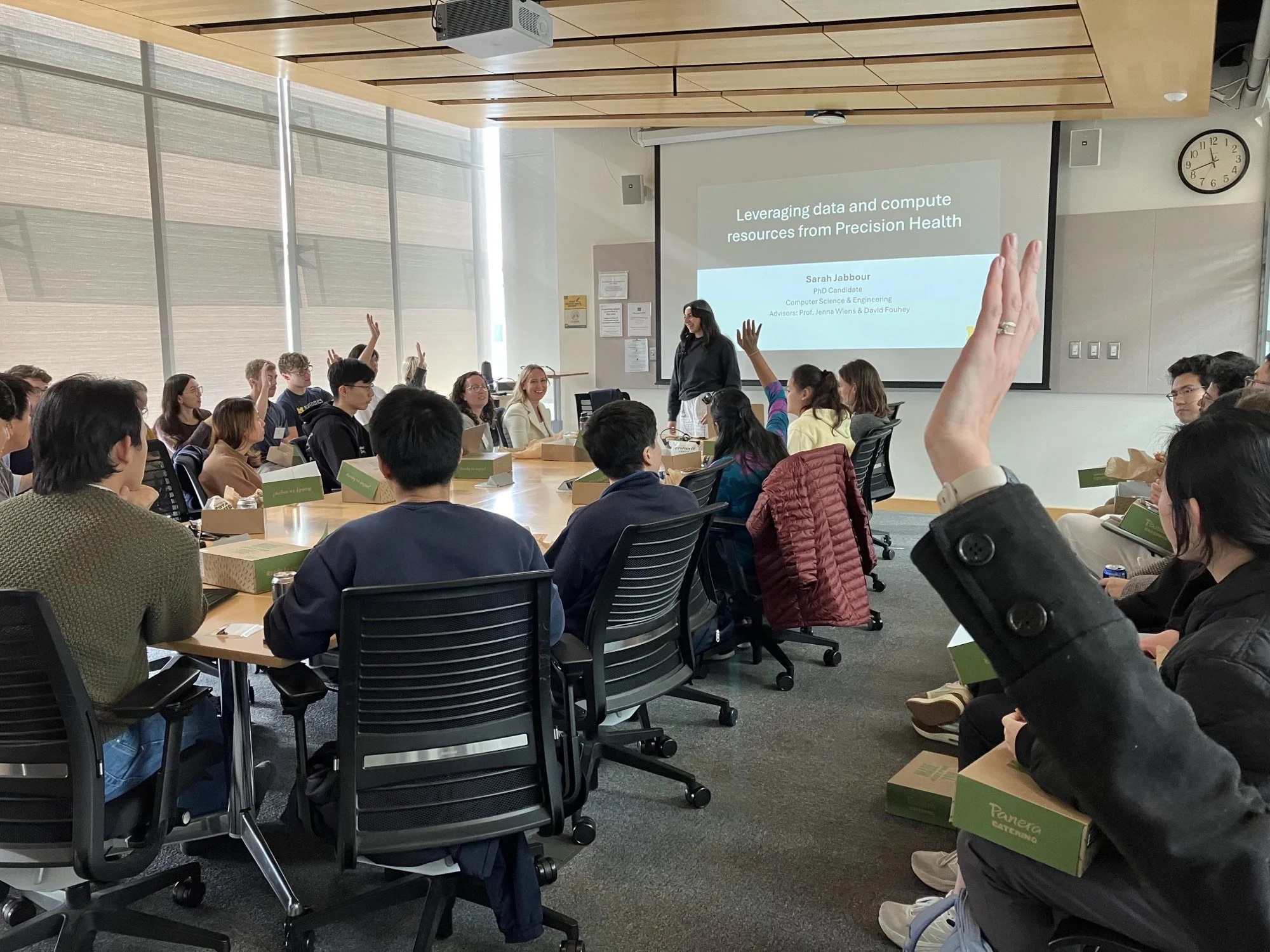

Our member communities provide forums to share health AI research ideas, foster innovation, and strengthen proposal development initiatives. Members are extremely active in their community and provide support for their peers in addition to seeking help with their own research.

Member Communities

Our team of health data experts works closely with members to define data requests to meet their research needs. If you need help getting data for your research project, let us know and we’ll get you started on your way!

Data Services

We partner with U-M Advanced Research Computing (ARC) to provide secure environments for processing and storing data for your machine leaning research. These valuable resources are FREE to all U-M researchers!

Computing Resources

Our Research Implementation team provides expertise in implementing research for testing at Michigan Medicine. From prospective data integration to workflow implementation and randomized control trials, we help get your research in the hands of clinicians, allowing you to validate the results of your research.

Clinical Workflow Integration

The Latest from AI & Digital Health Innovation

“With its robust foundation in data services and secure computing resources, expertise in guiding clinical workflow implementation for AI/ML models, and a strong culture of multi-school and interdisciplinary collaboration, AI&DHI will drive critical efforts focused on health at U-M and contribute to the upcoming transformative initiatives that will place U-M as “Leaders & Best” in AI for health.”

Marschall S. Runge, MD, PhD

Dean, U-M Medical School

Executive Vice President, MEdical Affairs, University of Michigan

Chief Executive Offiver, Michigan Medicine